PRINCE CUT

Type

Site-specific architectural cut / wall trepanation

Location

1021

Prince Street, Washington–Alexandria Architecture Center (WAAC), Virginia Tech, Alexandria,

Status

Semi-Permanente intervention (will be removed; documented through photographs)

Team

Project Co designed with Paul Emmons

Project Co executed with TeamWei-Chen Hung

Structure / Method

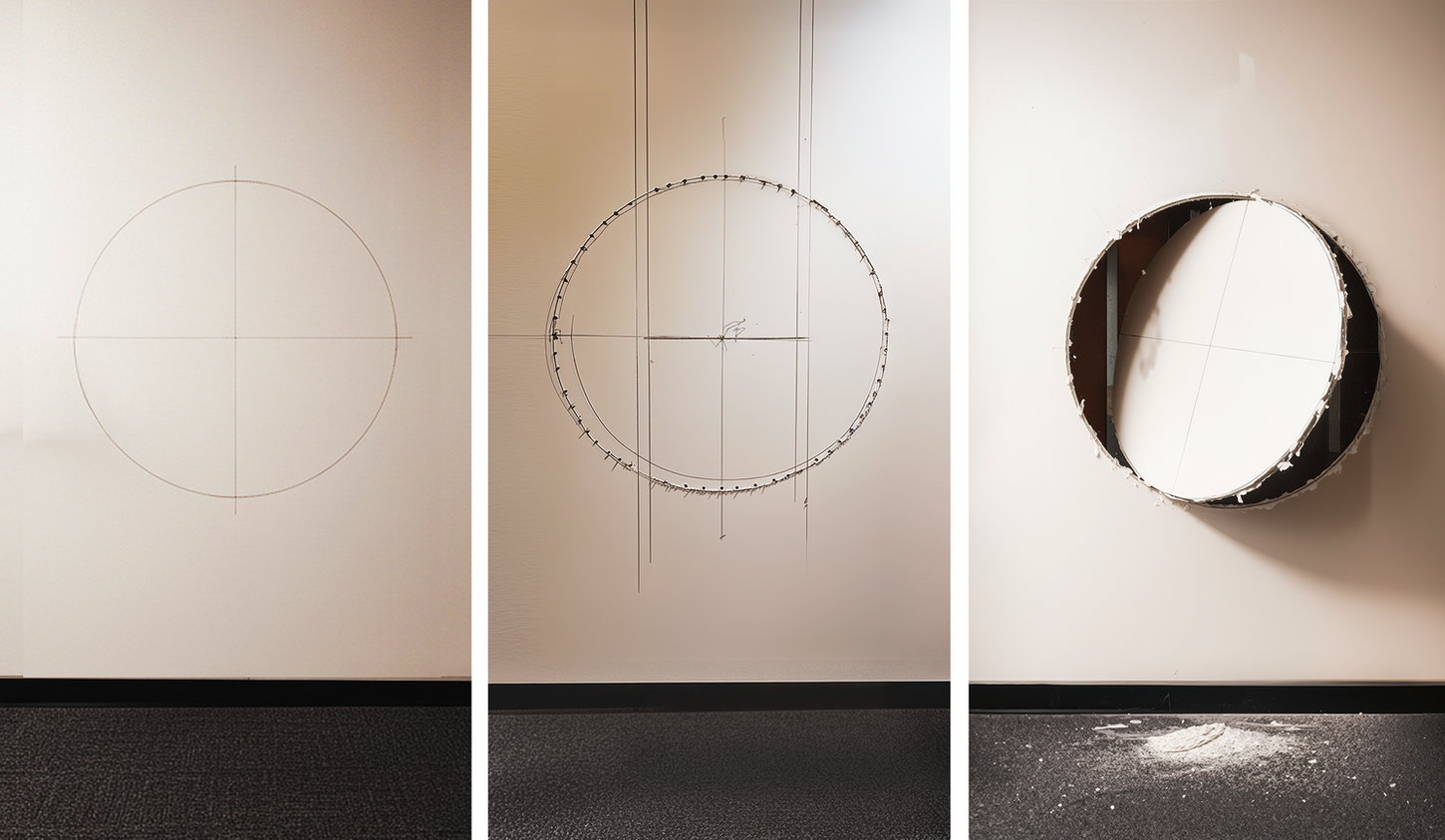

Conical wall cut passing through multiple rooms: compass-drawn circles, dense ring of drill holes, keysaw excision through gypsum board and metal studs; floor and ceiling layers peeled back to form a slanted light cone.

Materials

Existing gypsum board partitions, metal studs, insulation, carpet and ceiling tiles; graphite and marker layout lines; construction tape used as quipu-like tracer of the cut on the surface.

Funding / Research Framework

Produced as part of “A Broken House”, 2024–2025 Initiated Research Grant (SIRG), College of Architecture, Arts & Design, Virginia Tech.

Related Conference Presentation

Core ideas and images from this project fed into the paper “Katagraphics: Gilded Scars, Unruly Objects”, presented at the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand (AAANZ) Annual Conference: Unruly Objects, University of Western Australia, Perth, 3–5 December 2025.

the urge to be at home everywhere.

— Novalis

The Prince Street wall cut treats the building as a skull that needs trepanation. A precise circular opening is scraped through paint, plaster, and gypsum until the metal bones of the office appear. The operation is slow and surgical: a nail at the center, a cord acting as compass, a ring of drill holes, then the bite of the keysaw. Each layer lifted away is a small exorcism, a release of whatever has been stored in the walls.

The form is a tilted cone of light that tunnels between rooms, floor and ceiling, earth and sky. The cut folds together many cosmologies of cutting: Inca cranial surgery as controlled wound and cure; Andean despacho rituals that open the ground to offer something back to Pachamama; Indigenous ideas of susto, where part of the soul remains trapped in a place. Here the building’s own susto is addressed by opening it, by letting it breathe.

The geometry is disciplined, but the exposure is messy: insulation, studs, stains, all the backstage of “professional” office space suddenly on view. The compass and the saw stage a duel between ideal and real—the perfect circle of architectural drawing against the jagged empirical cut. The intervention is both wound and instrument, an architectural trepanation that suggests that homesickness is not only a human condition but a spatial one: the building itself is trying to remember what it once was.